In earlier posts, I’ve shared that the last 5 years have been difficult ones for me emotionally. So while I’ve felt overwhelmed and stressed many times, reading the following letter written by my father, Chuck, and his mother, my grandmother Emma, on May 30, 1945 and sent to family and friends about their rescue during the Raid at Los Banos, has provided me with must needed “perspective.”

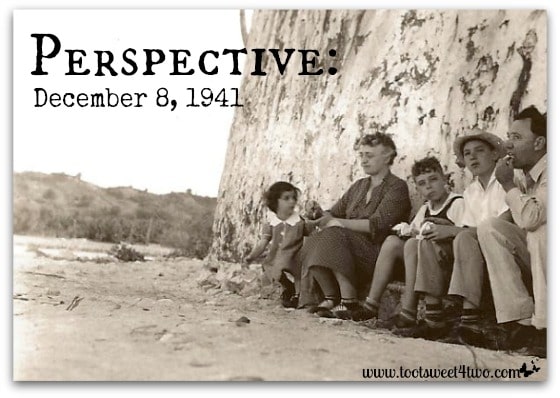

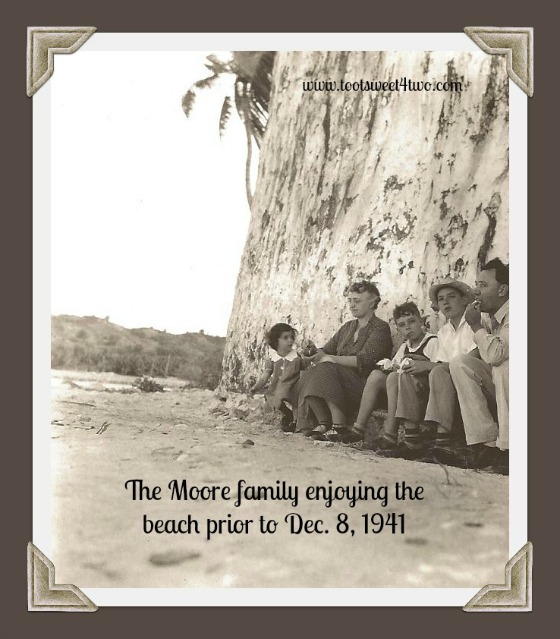

Photo above: the Moore’s on the beach – left to right: Patsy, Emma, Charles (Chuck), Joe Jr. and Joe Sr.

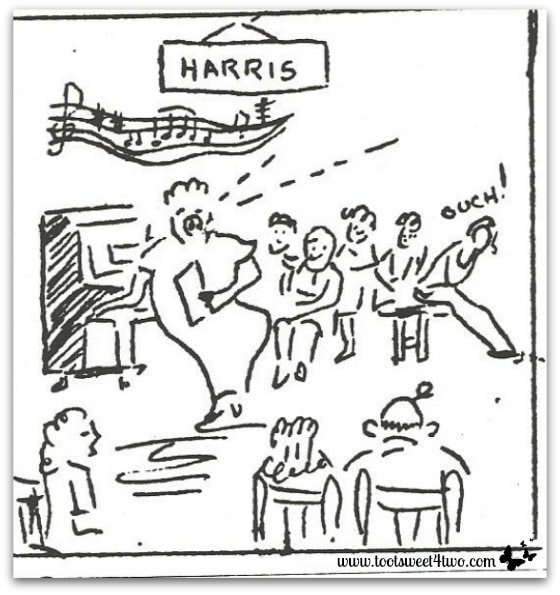

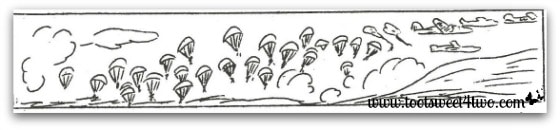

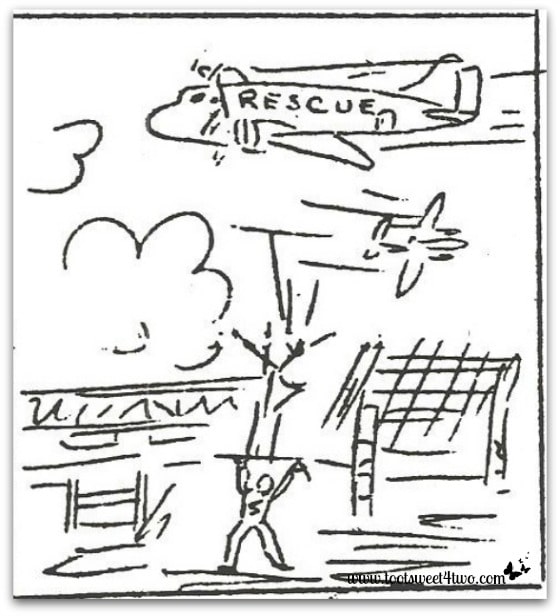

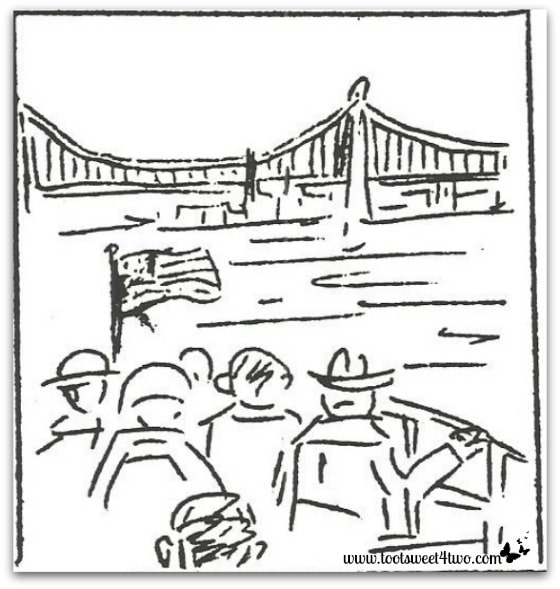

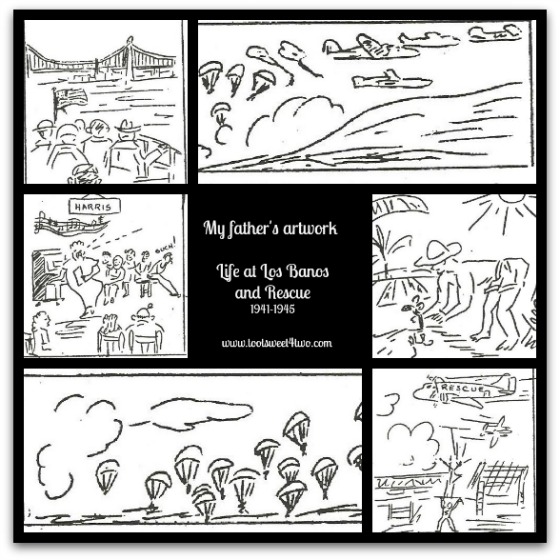

The story about the Raid at Los Banos is long but the pay-off, a peek into the world of 1941 to 1945 written from first-hand knowledge of unfolding world events, is worth the read. The simple illustrations were done by my father, 15 years old at the time of the letter, who grew up to become an Air Force pilot of C-130 aircraft. The impact of their rescue by American soldiers during the Raid at Los Banos left a lasting impression with him and a desire that fueled him and made his life-path clear.

This story is not only my father’s story and his family’s story, but the story of all the other internees at this Japanese prisoner camp that were rescued during the Raid at Los Banos. I have transcribed it exactly as they wrote it in their words.

Here’s their story about the Raid at Los Banos:

Berkeley 7, California

Written May 30, 1945

By Charles F. Moore with additional notes by Emma G. Moore

Dear folks and friends:

December 8, 1941: The war was on with Japan. Joe, Patsy and I left school early that morning, bringing our books home with us. Manila was expecting an air raid that night and it came. At midnight the sirens wailed – no bombs. But a couple hours later we heard the planes – the bombs!!, and then the siren.

We had been told to go to Baguio, as it was believed safer from bombing. We packed the next morning and were off by one o’clock. It took us most of the afternoon before we reached the zig-zag road on the mountains. On the way we waved to many truckloads of Filipino troops being sent north. That night we slept in the car at the foot of the zig-zag, because we could not see to drive during the blackout. The next morning early we drove into Baguio, and settled down in a cottage on the Methodist compound and watched the Japs bomb Camp John Hay.

On December 22 we got word that the bridge crossing the Agno River was going to be blown – this would cut us off from Manila. We packed up quickly and started back to Manila. An air raid was on even when we started, and on the way down the canyon, a bomber flew over. At night we stopped in Villasis, which was being guarded by a small force of soldiers with tanks, half-tracks, radio truck, and motorcycles. The next morning early we were guided over the huge bridge by a Captain on a motorcycle. The bridge had already been loaded with dynamite.

We made Manila safely and settled down, trying to adjust our nerves to the Japanese bombing of the Port area, which was done every day. The bombing continued even after Manila was declared an open city. We celebrated our first Christmas with a war going on, but we kept cheerful.

By the end of December all the Methodist missionaries gathered at Harris Memorial Training School, to set up a sort of community way of living during the war. The Japs came into Manila on the second of January and immediately began to round up the Americans and British to intern them. The University of Santo Tomas was chosen for the main internment area and we with the other missionaries at Harris were taken in for five days. We were then released from internment.

(Note by E.G.M. — The interned missionaries did not seek release. The Filipino Christian people were upset because of the action of the Japanese in putting their missionaries in prison. In releasing us the Japanese asked us to refrain from any military or anti-Japanese activities — this was the same thing they imposed upon those who stayed in Santo Tomas.

Needless to say, we did engage in forbidden activities — this we considered our business, if we could “get by” with it. We were able to help the guerillas and war prisoners with food, clothing, medicines, etc., through routes kept very secret.

While we were released to “cooperate with religion”, this was but a formality — they and we ignored it. There were many fearless sermons preached by missionaries and Filipino pastors, bolstering the courage of all who came to hear. My husband preached regularly in a small church. Then we had many heart-warming experiences of prayer and mutual assurance, whenever our Filipino friends ventured to call on us in our one-room apartment in Harris. These visits were high-lights during our Harris days, for they revealed the courage, steadfastness, loyalty, and faith of our Church people, who kept coming into our restricted compound with gifts, both material and spiritual, determined to carry on, and help us carry on, during years of oppression and sorrow.)

Charles continues: At once we set up an economic way of living at Harris. Committees were appointed to do the various things that were necessary. There were the executive, garden, building and grounds, school, kitchen, worship, and recreational committees. Everyone was on a committee. Joe, Patsy and I kept up well on our school work, and for recreation we would play indoor tennis, ping pong, baseball, kite flying, football (in a small way) and other sports. Mother led a weekly music class – “The Enjoyment of Music” – and every one at Harris was welcome to attend. Most of them came regularly. She also invited some of our Filipino friends. The class included history of music, music forms, folk music and so on, and there was always group singing, some solos, duets, trios, and the small children did delightful numbers each week. Joe and I gave solos and duets on our instruments, the violin and clarinet.

(E.G.M. — Joe and Chuck performed nearly every week and I depended upon them for most of my illustrations covering my talk. J.W. sang many of the beautiful classic songs needed for illustrations. Eleanor Riley sang [I gave her voice lessons] and the community folks helped generously by working on the vocal ensemble numbers which I assigned for lesson illustrations. We also had a course in Hymnology running through three months.)

Charles continues: Food was hard to get and expensive, but we managed to keep fairly healthy, although we couldn’t get enough of some of the essential foods like milk, meat, eggs, and bread. Patsy had two serious illnesses of dysentery and trench mouth, and there was other sickness of course.

Life went on and on at Harris this way. The kind Filipinos helped us all they could or dared. The Japanese kept close tabs on us and the adults were required to submit a weekly report on their activities. We were not allowed to go out of the compound except to purchase food, see the doctor and dentist, or go to church.

Joe and I went out to take music lessons about the second year. This going out was not included on the pass but we went anyway. But finally I was stopped on my way home by Jap military policy, questioned, threatened and scared. The folks received a warning notice. So we stopped the music lessons. But we kept up our practice for some time, continued up our community school, and worked in the garden. In the garden, we first had to clear out stacks of rubbish, broken china-ware, old tins, iron scraps, etc. Then we dug it up, and raised beans, tomatoes, cabbage, cauliflower, onions, squash, eggplant, and many kinds of native greens. We saved quite a bit of money by eating from our own garden. To water our garden we dug two wells, each about 8 feet deep. Water was struck at about 4 feet. Dad was the one who really dug the wells and hung the well sweeps for pulling up the buckets of water. Of course, Joe and I helped. We boys and Dad had a great time out in the sun. We soon had dark brown skins. Dad kept busy from morning til night repairing many needed things around the place, making screen-doors, rebuilding furniture, fixing water closets, poisoning termites, digging the garbage pits, mending the wooden shoes for the ladies, etc. He was the buyer of fruit for the community and went to market several times a week.

The day arrived when the Japs became uneasy. On the night of July 8, 1944, military police came to Harris and told us we were to be ready by nine the next morning, to be interned in prison camp. So the next morning they took us to Santo Tomas. That night we slept on the floor of the big gym, and were sent on by train the next morning to Los Banos. There were more than 500 of us, – religious workers of many different churches, who had, like us, been out on passes. At Los Banos there was already a camp of Americans. We were housed in long barracks of nipa and sawali, (palm thatch and woven split bamboo) each housing 98 people, 2 persons in a cubicle of 8 by 13 feet. The partitions were less than 7 feet high. We were not allowed to contact the other internees at Los Banos. However, it was done on the sly.

The food the Japs gave us was very poor — mostly rice, a few vegetables and a very little bit of meat. At first we had enough to keep off hunger, but the amount was reduced as the weeks went by, and for the last six months or so, the daily number of calories was 800 or less per person.

The camp was run by a committee of Americans who dealt with the Japanese authority. There were special work details and every internee was required to do his part to keep up the camp. There was the kitchen crew, wood crew (for providing cooking fuel), the garden detail, school, grounds, carpentry, plumbing, etc. The camp was like a village, or two villages until the Japs decided that it was too much trouble to supply two different kitchens. So the two camps were finally united in September. At this time a Japanese garrison moved into the vacant barracks and building, about 60 of them.

Joe, Pat, and I attended school. I worked in the community kitchen as a mush cook and with another fellow cooked the breakfast mush three mornings a week, getting up at four a.m. Joe was a fire stoker and helped build the huge fires under the cooking cauldrons. He went on duty at 3 a.m. The breakfast for 500 was 26 buckets of corn mush. Those who happened to have some sugar, could enjoy semi-sweet mush, but most folks ate it plain. It was really poor, but we had nothing else. In the afternoon we worked in our own struggling private gardens raising greens and beans for supplementary food. The soil was poor but we did the best we could.

A Catholic priest, Fr. Alfred, who was the friend of all children, started a class in tumbling. Joe, Patsy and I were in the class with 6 other boys. We learned to dive, roll, turn a forward flip, etc. Before we were too weak from malnutrition, we put on a show. Every one in camp came, and we were a great success.

The Japanese squeezed the money from the internees through the canteen, but the canteen was the only source of extra food. The internee committee purchased food from the Japanese authorities, getting what they could at heavy prices. Often we couldn’t get anything. We stood in line for canteen, as we did, of course, for our meals. Then the Japanese shut the canteen off. Meanwhile the chow was getting worse, and less and less. We were getting around 700 calories a day in November. The Japanese were becoming irresponsible and restless. It was no wonder. The Philippine campaign was on! Every day we heard or witnessed aerial activity. American planes swooped low, and our morale shot up. We cheered every plane. The Japs were steadily cutting the rations down and we were getting weaker and weaker. Then…..

One morning at 3 o’clock a voice shouted through our long barracks. “Get up! The Japs are gone! We’re free!” It was true, the Japs in charge of the camp had turned the camp over to our Committee and had pulled out. There was a rumor that there had been a landing on the Batanges coast. For five days the cooks gave us lots of extra food and everyone began to feel better. The camp listened to President Roosevelt speak over the radio by the loud speaker system and there was a flag raising ceremony. Hundreds burst into tears when the Star Spangled Banner was played. But then to our great disappointment the Japanese command came back and took over the camp with even a sterner hand than before. That was the end of our “Freedom Week.” We got less and less food.

Finally we were handed out a small quantity of unhusked rice which we had to husk ourselves — a very difficult, slow job by hand. The Japs had shot two men who had gone out of bounds to get some food. They were harsh and cruel. Joe and another boy were marched off to the Jap office in front of bayonets, because they climbed a tree to see the American planes better. They got out of this difficulty, however. We were required to line up for personal roll call twice daily, morning and evening. We were warned that escape meant death, but several men left camp one night and were not caught. It was said that these men contacted the guerillas and the U.S. forces and helped plan our rescue. By this time Santo Tomas had already been liberated, although we did not know about it, but we were hoping for and expecting our release soon, before more people succumbed to starvation.

Raid at Los Banos

On February 23 we got up early as usual, to be ready for seven o’clock roll call. At about seven o’clock I went out to our cook shack to cook the last of our polished rice (saved from Freedom Week distribution) for breakfast, when the roar of low-flying planes came to me. I looked up, and half a dozen C-47’s dropped their load of paratroopers, 150 in all, right into the laps of the Jap garrison a mile and a half northeast of camp.

Then machine guns blurted and bullets whizzed overhead. We all lay down flat on the floor and shivered when a bullet struck the barracks. But our rice on the outside stove was burning and we were so hungry that we couldn’t let it go to waste. So I ducked out to the cook shack and stirred it. Just then a C-47 swooped low and on the side of it was written in great letters the word “Rescue”.

Wow! This was IT! After 20 minutes the shooting stopped and a swarm of amphibian tractors rolled up the roads and onto the camp turf. We were told to take only what we could carry. There weren’t enough Amtracs to give every internee a lift, so many of us, including Dad, Mother, Patsy and me, walked the three miles to the shore of the lake, where we waited to be taken across on the second loading of Amtracs. Joe with his badly cut ankle, was unable to walk, and two guerillas carried him to an Amtrac, and he was taken across the lake with the first load and put right into the hospital for ten days of treatment.

This rescue had been planned and timed to the minute. As soon as the paratroopers jumped, the guerillas, who had surrounded the camp the night before, were to fire on the sentries and seize the camp. The guerillas were commanded by a G.I. Captain and 14 other U.S. soldiers. The attack was timed to catch the sentries when they were being relieved of their post, thus getting two shifts instead of one. While the guerillas were dealing with the sentries, the paratroopers wiped out the garrison and then came up and covered the camp while the Amtracs carried the internees aways. The G.I.’s leading the guerillas threw phosphorus bombs into barracks 3 and 4 where the Japs in charge of the camp were living. This smoked them out and set the barracks on fire. As the Japs scurried out of the inferno, they were mowed down by the guerilla fire. The burning barracks set fire to others near by, and the camp was soon a scene of burning nipa and sawali. All this time P-38’s covered the action below and no Japs ventured to come into sight. By afternoon we were safe at the army base on the other side of the lake. By evening we arrived at New Bilibid Muntinglupa by truck. This was to be our new camp until we could be repatriated.

At Muntinglupa we stood in long lines for meals, but what difference the meals were! Three good square meals of army chow! Everyone began to put on weight. There was milk for the younger children, movies in the evenings for everyone. Several dances were put on for the G.I.’s. Many of the boys had not seen a white girl in so long that they were shy about asking the rescued girls to dance.

After two weeks, it was announced one night that all the single and unattached men would be repatriated the next day. Joe and I thought, “da sooner da better!” So we got in line, and the next morning we were trucked to Nicholas Field, where we were assigned to a big two engine transport plane along with 38 other internees. The big C-46 took off about two o’clock in the afternoon. We circled Manila and landed on a highway in Quezon City for a few minutes. We took off again and circled Manila once more. We could clearly see the ruins of Manila and the great numbers of sunken vessels in the bay. Then we headed for Mindoro. I got acquainted with the pilot and co-pilot and when we neared Mindoro the pilot offered me the plane to fly for 8 minutes. It wasn’t very difficult to keep the big ship on a straight course for I was instructed by the co-pilot as I flew. Boy! What fun! The pilot then took over and landed in Mindoro. The army set up a huge air base there — there were hundreds and hundreds of planes on the ground and in the air, P-38 Lightnings, P-51 Mustangs, P-45 Thunderbolts, P-40-N Warhawks, B-25 Mitchells, B-24 Liberators, A-20A Havocs, B-17 Fortresses, and P-61 Black Widows.

It rained the next day and our plane couldn’t take off, so we stayed there two days before the strip was dry enough. Then off to Leyte, in the early morning. We climbed to 14,000 feet. It was cold up there. We traveled at about 165 MPH. When we neared Tacloban, Leyte, the plane sank into a low fog bank and the pilot was lost for a few minutes. He had considered putting us down into a rice paddy because of the danger of running into the mountain on the east side, but he pulled the plane up and over the mountain and fog instead. It was taking a chance! When we landed, I looked out into the bay and saw scores of ships. Tankers, troop-ships, and warships.

We were put in tents at the rotation camp and waited there a week before we were put on our ship. We waded ankle deep in mud because it was swamp country and it rained almost constantly. Nobody was dry. On Leyte, we were issued clothes and shoes, and we signed affidavits, etc. At last we were loaded on one of our Army’s super transports. And on the 18th we sailed for San Francisco. The trip was uneventful, but we passed the time sleeping, eating, reading and drilling. The food was good, but we were too hot to enjoy it. We stopped at the Admiralties, Pearl Harbor, and then – San Francisco! After eight years in the Philippines, 22 days on a ship, the Golden Gate was a welcome and thrilling sight. Even if it was a foggy morning we stood shivering on deck, cheering with the others as we sailed under the bridge. Home at last!

E.G.M. writes: After our sons Joe and Charles left by airplane for Leyte, Dad, Patricia and I stayed on a month longer at our Evacuation Hospital camp, devouring quantities of good American food. Patsy and I slept on army cots with about 50 other woman and children in one dormitory room of the prison compound. Dad was on the same floor, in a similar room, full of men. The army issued each of us a cot, towel and two blankets. The Red Cross issued a tooth brush, tooth paste, comb, and some limited articles of clothing.

We longed to get off for home. When the big day arrived, we were loaded on trucks for Manila, there we were taken out to a great troop ship, the Eberle.

On board ship we had good food and friendly care. Many of us were weak, so standing in long lines for food, eating with the perspiration rolling down fast in the midst of tremendous crashing of dish-washing and confusion, was very fatiguing. Each day we climbed 22 to 30 flights of iron ladders making the necessary trips to chow, bath, top deck, many times over. But we were glad to be on our way, any way. Pat and I were on the top bunks in the tiers of cots set up bunk style, and we were five decks below the boat deck where we were allowed to sit down in the open air.

But we got home — we arrived in San Pedro May 2, early in the morning. Patsy, ill with bronchitis, was taken ashore on a stretcher and transferred to the Methodist Hospital by Army ambulance. Dad and I disembarked about 4 p.m. The Los Angeles Red Cross received us all in a marvelously efficient and friendly way. We were taken to L.A. in buses, were processed at the Elks Club, finishing the necessary business there by twelve midnight. Methodist representatives took care of our immediate financial needs and were helpful in several ways. The next day, we had further business at the Red Cross Headquarters, did a little shopping, and drove out to the Methodist Hospital to see Patsy. Thursday evening we spent until midnight at the doctor’s office on medical examinations, by order of our New York office. Friday morning we were again at the doctor’s office. Friday, after a little shopping, we visited Patsy, then were taken to Hollywood for dinner by delightful new friends, the Goldfarbs. They took us to a swank place, and we had fun!! Next day was largely spent in line up for our train reservations. The Red Cross tried to get all the returned internees out of L.A. by Saturday evening. Our reservations, which we finally received by about 4 p.m. were for Sunday morning.

We had supper with our cousin, Mr. Traber, at his hotel, visiting him that afternoon and evening. Sunday morning, we picked Patsy up out of the hospital, boarded our streamliner at 7:15 o’clock.

Sunday evening we arrived at Berkeley, where we were met by daughter Clara, and her husband Al, baby Joe, our sons Joe O, and Charles, and cousin Harry Butterfield and daughter Marjorie. How happy to be all together again!

Both Clara and Mary Butterfield are feeding us so well that we are all putting on pound after pound. We hope that before long we will all be in good condition again.

This news letter has left many things unsaid. We wish we could see you and know how you are. You, too, have had your war years, with many hardships. When we thought we were having hard times we always remembered that the people in Europe were having harder times, and that many of our folks at home were sending their sons out to battle for us all. We had only to wait and get through, somehow. But they carried the heavy load for all of us. We have not forgotten, and have remembered you in our prayers, for the early coming of victory and a new era of peace and good-will.

Sincerely,

Emma G. Moore, May 30, 1945

7 Minutes from Death

What the above story doesn’t tell you is that the prisoners were due to be executed at dawn – to quote another survivor’s story that I read on-line, “we were 7 minutes from death.” Without the precision and implementation of a well-conceived and executed military operation, the Raid at Los Banos could have happened minutes too late.

When I read this for the first time, many years ago, I had just seen the movie “Empire of the Sun”. Uncannily, my father’s and grandmother’s story tracks with many of the story lines depicted in that movie. “Empire of the Sun” is about a British boy living with his family in Shanghai. The Japanese invade Shanghai and the boy is separated from his family and eventually ends up in an internment camp in Shanghai. Although my father was not separated from his family and my family is American and not British, and they were interned in the Philippines and not Shanghai, the story is eerily similar.

Here’s a link to the Raid at Los Banos on February 23, 1945. Without the heroes of the 11th Airborne Division, the other supporting military personnel and the Filipino guerillas who participated in this rescue mission, I would not have been born. Now that’s “perspective.”

Do you have similar family stories to share?

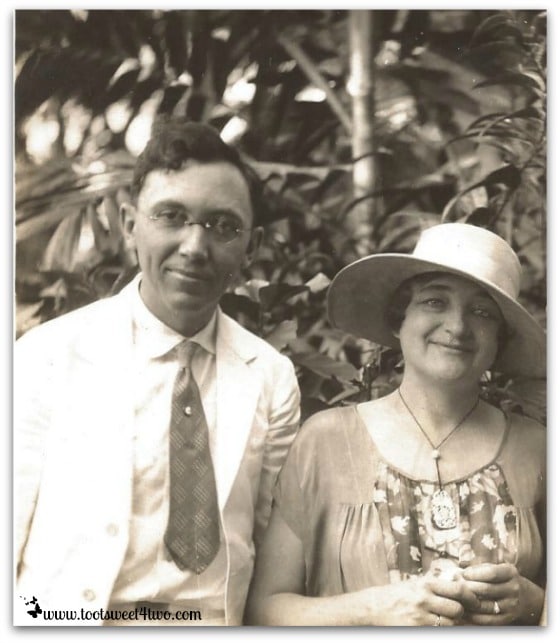

Happier times hiking in the Philippines before internment and the Raid at Los Banos in 1945.

My grandparents – Joseph and Emma Moore

Sketches of the Raid at Los Banos rescue in 1945

Until Next Time,

Thank you so much for sharing your family’s story. I am in tears.

Thanks, Terri, for taking the time to read it because it is a long post, thus a “commitment”! But helping to keep the past alive is an important part of our future.

I had no idea your wonderful Dad and his family had been through so much.

Simply incredible and clearly it helped make him the extraordinary man he was.

His ‘down to earth wisdom’ taught me so much.

Big love to you and your family. Gina x

Thanks, Gina, for your comment. That was part of what made Dad so great – his humility and not letting the past hold him back. He inspired us to be better, to do better.

Carole I have goosebumps and tears….what a tremendous story.

I love yours and Tiffany’s blogs, thank you for sharing all you do.

Sending much love Gina xx

It’s his story – I just gave it “perspective”. Often in our toot sweet life, we forget to honor the people who have paved the way for a better life. He and his family’s story is the story of so many prisoners of war in the past, in present time, and in the future. Love to you and all of the family at Hall Farm and in London!

Amazing. It’s so great to have this family history documented, even as tragic as it was. Thanks for sharing. Take good care.

Thanks, Anna. Yes, the family history is important. I’m sure we’ll come across other history that I’ll share! Love you!

Thanks so much for passing on this story to our descendants and to others. It’s even better knowing it is in Dad’s own words. I have a copy of the letter too somewhere, but haven’t read it in many years. Love you (and Mom and Dad)

You’re welcome! Love you, too!